Let me start with a question, how many software engineers do you know that enjoy Frontend development?

One question has always baffled me – Why is frontend universally unloved?

Let’s throw a few suggestions:

Is it the juggling between 3 “languages” – HTML, CSS, JavaScript?

Is it the messy CSS and inability to vertically center a text in a box easily in 2019?

Is it the inconsistent browsers’ feature support and rendering?

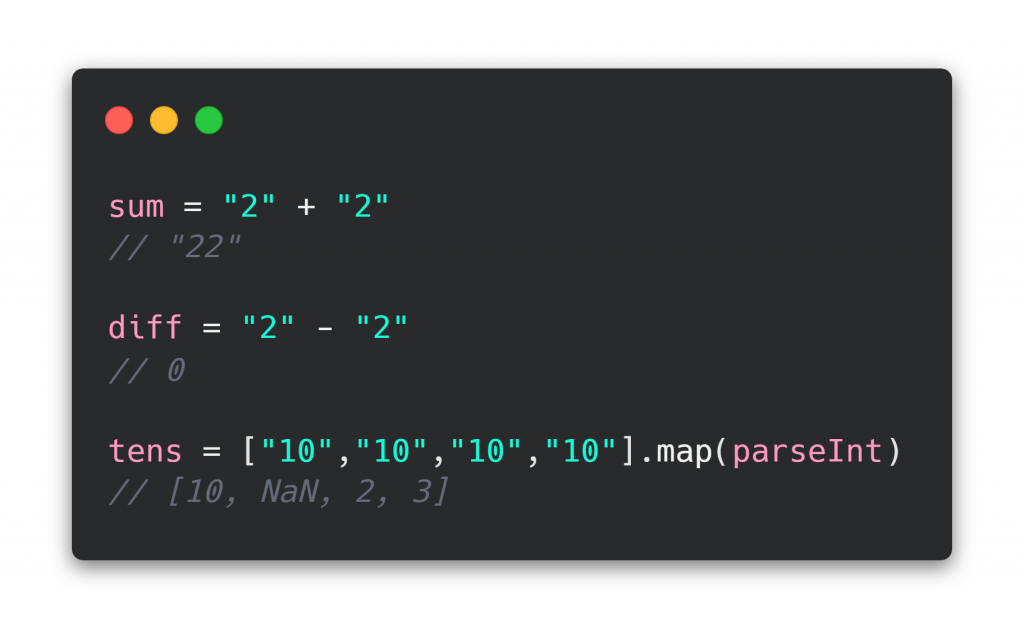

Is it the JavaScript “funny” parts like:

Is it the “move this by 3 pixels to the left” expectation of people who’ve never done it?

Is it the tooling and the amount of frameworks required to do the simplest things?

Reality is, it’s all of the above.

The more people I ask, the more frequently I hear – I’ve just always been a backend developer.

Great, but why not have a go at frontend? I suppose it’s the myths and legends people have heard about the amount of frameworks necessary. Yes, JavaScript and its ecosystem are in a weird place right now, but that’s a topic for another time.

I recently set up a pipeline for a web application from start to finish.

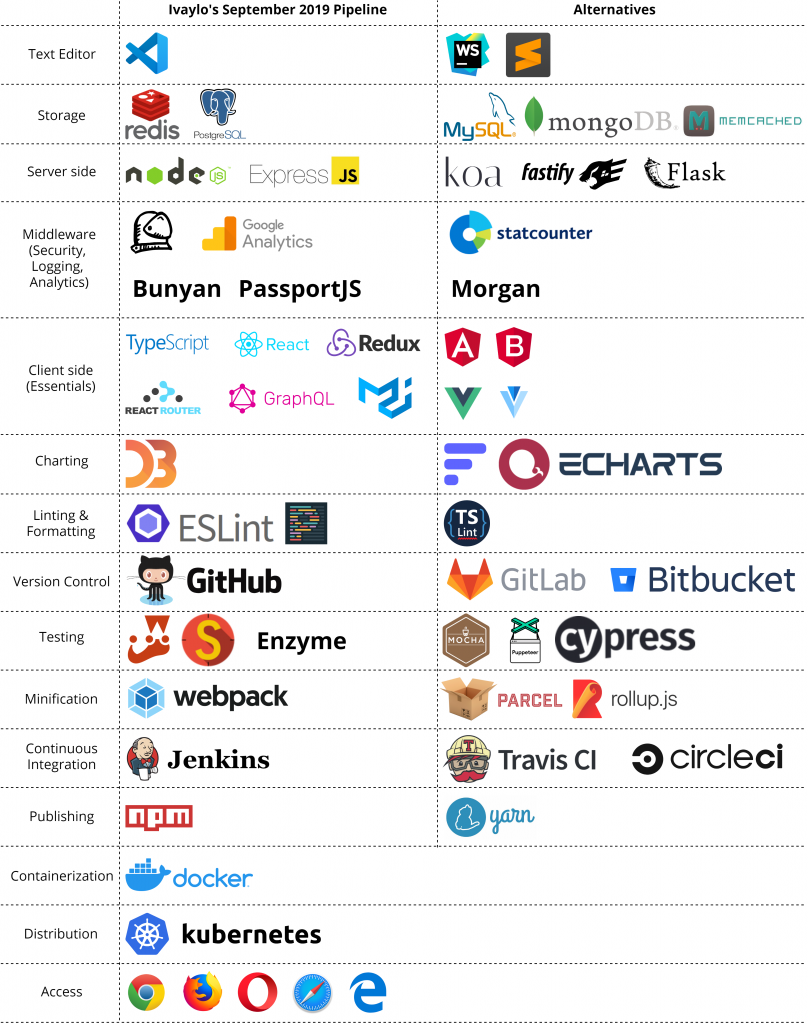

To illustrate where web app frontend development is at (September 2019), I put together this table.

If I told you, in my eyes, this is the absolute sensible bear minimum for a web app, that’s not from a standard template using Jekyll, WordPress or such. Would you believe me? Unlikely, but let me try to convince you.

Frontend is Complex

Looking at the image above, you can argue that I’ve included backend and SRE elements. Sure, but if you design a small project at home, you would still need to deploy it. If you want to store session data, you might opt in for Redis, instead of cookies. Flask is also Python-based, but for our illustrative purposes it’s not important. I agree the above table is not perfect. The point is – when is the last time you started a backend project and needed that much decision making in advance about frameworks that are not in the standard library. What confidence do you have the stack you’ve picked today will be the right one in 5 years time?

What makes frontend fundamentally different from backend is the amount of control over the moving parts which you need to integrate and make for a seamless user experience. You are also heavily limited by language of choice. You can create a User Interface in Python, but the ecosystem for that purpose is not there.

Frontend is an amalgam of multiple backends, teams, their design philosophies and system infrastructures. You are definitely not in complete control of the downstream. Yet you need to make it all seem as one coherent interface to the user. End goal being nobody realizing, one of the endpoints is 30 years old written in a language that nobody understands and another a 2 week old one that is not battle-tested.

You also need to think of security – HTTPS, SSO, 2FA, GDPR. I can continue with the acronyms for days.

Testing

Testing backend is certainly easier, you have a limited set of inputs, you confirm the outputs. Testing something that can have an infinite amount of mouse movements, states, rendering behaviors, screen resolutions, network inconsistencies and a random sequence of steps is another ball game. Can you guarantee that none of the endpoint have no side-effects? Which is probably why there’s so many testing frameworks. You can see the list on BestofJS and that one excludes integration testing.

Fragmentation hidden behind choice

The first time I picked JavaScript was in 1999. There was only one framework that ruled the world and it came out much later – 2006 and it was called jQuery. So what has changed between then and now – the medium and the demand. The web is no longer bound to a single desktop screen showing static data. We now have real-time sports scores, video streaming, data stored and consumed multiple magnitudes larger than before and apparently we are on the road to producing 163 zettabytes of data yearly by 2025.

The proliferation of solutions to these problems – HTTP v2, Websockets, ReactJS to name a few is actually a great thing. These are the results of growing pains, in 2006 I used to do PHP and haven’t touched it since, then it was Ruby and nowadays it’s just ES6 or TypeScript. After all that growth, we never really reached the point of consolidation in the JavaScript ecosystem, the massive redundancy of libraries in NPM and a Node Modules folder of more than 10,000 files are a testament to that. I believe things might be turning around. A perfect example is Palantir’s TSLint module that is soon to be deprecated in favour of ESLint with support for TypeScript. You can read more on this here. A project I’m following with much interest is GatsbyJS. It’s essentially a large chunk of the pipeline above combined in one out of the box, hassle-free setup.

Micro Frontends Design

A lot of the above issues exist, because UI development is this umbrella covering the entire backend. In many cases, backend teams wouldn’t have full understanding on how their endpoint is used in the user interface.

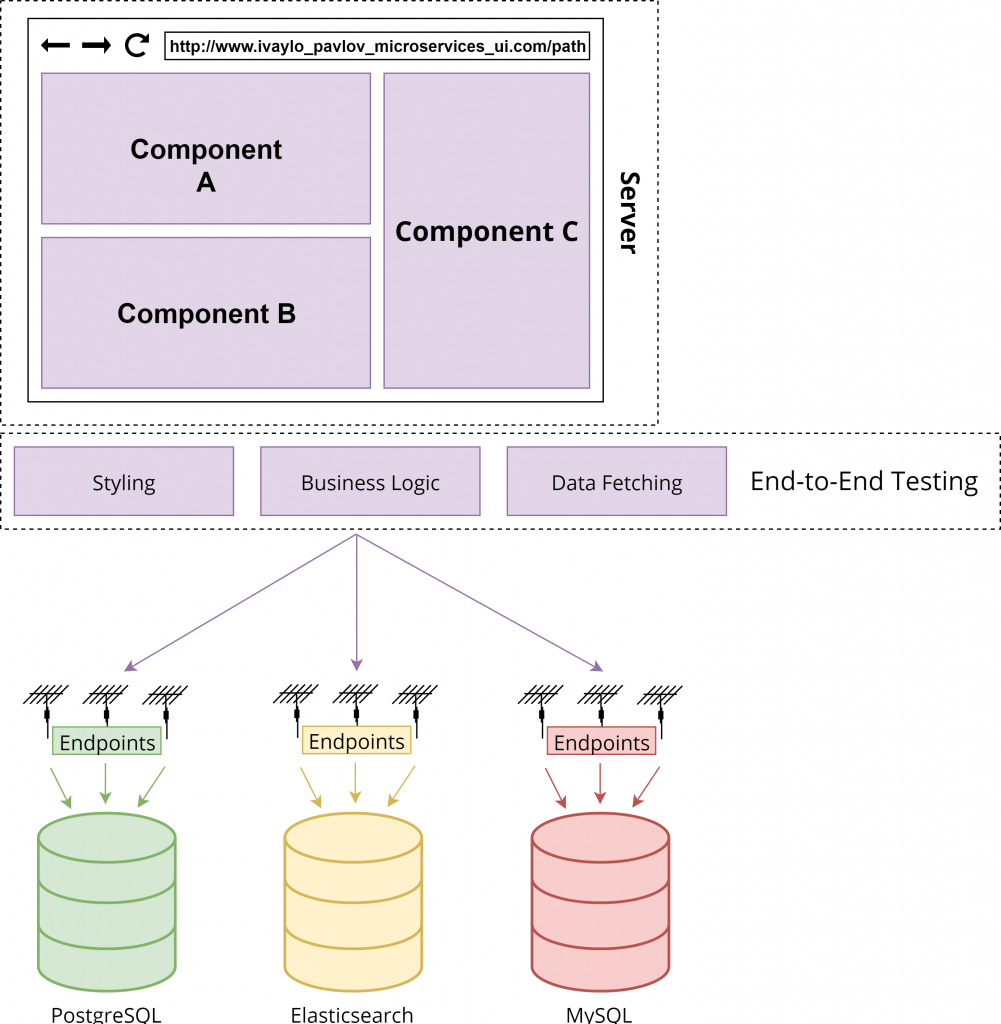

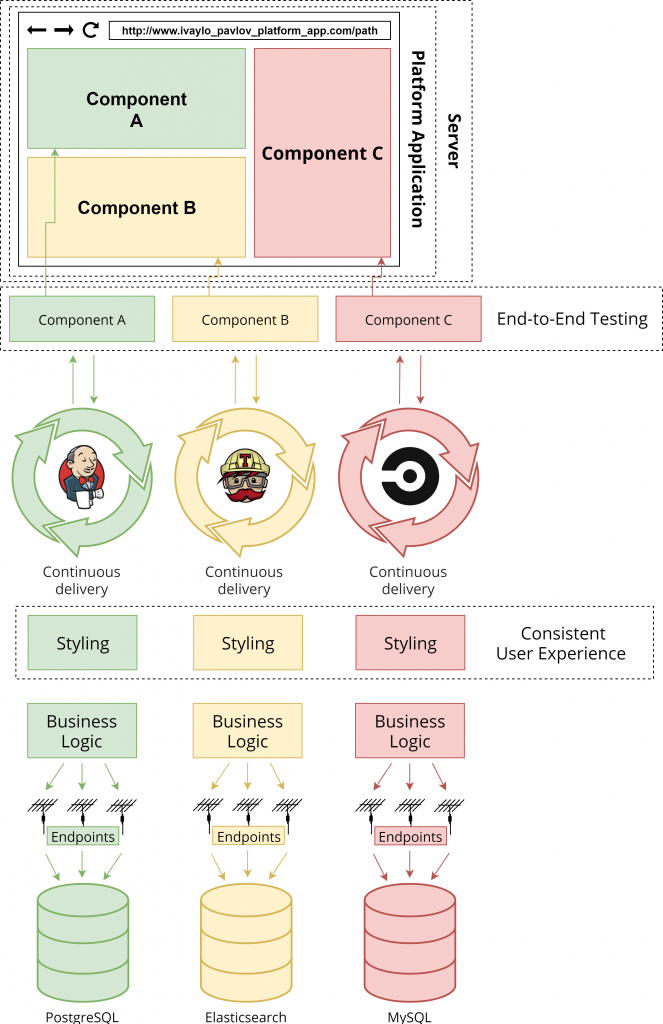

I strongly believe the future is Micro frontends. It’s the principles of microservices architecture extended to the frontend. Each team owns the entire pipeline, from data store, backend, endpoints up and to the displayed user interface component. ReactJS, for example, is well suited for this type of design. I’m better at doing diagrams than writing, so here’s a comparison between the current microservices and the new micro frontends designs.

Microservices Design |

Micro Frontends Design |

|---|---|

|

|

Build-time vs Run-time integration

In all cases you need a platform application, which will bring everything together. It also includes basic elements, like header menus, about and FAQ pages. The question is how it will bring it all together.

Build-time integration

This is when each team deploys their components as a part of a NodeJS package to the company’s artifactory and then the platform application imports them. The good part is that it deduplicates the dependencies when minified, but the teams’ deployments are dependent on the main app’s team release schedule.

Run-time integration

It offers complete deployment autonomy, but each team needs to take care of the styling themselves. Don’t do iframes, you can, but don’t. The proper way is to import bundle JavaScript files in your index.html file via the <script> tag. Each micro frontend should give you a global entry-point function, which you should have negotiated in advance and the platform app, just points where to render the component. The state management and routing become less of a pain compared to iframes for the platform app team. However, you download the same dependencies multiple times, as each component’s code is unaware of the rest.

My personal choice is build-time integration.

The main reason is to enforce consistency. The platform team will also be in charge of the general end-to-end testing, as well as enforcing uniform styling on the components if one team has not followed procedures. Complete autonomy sounds great, but also allows to get inconsistent user experience very fast and for things to spiral out of control. Secondly, even with run-time integration, you need to negotiate interfaces and state, so even though you can release any time, your feature still needs to live behind a feature flag or branch out. So in reality, you don’t really lose that much deployment autonomy. Also, with a good CI/CD pipeline, any component contributing team should be able to do a test branch deployment with the platform app and be able to test their component in real-world like scenario as part of the whole. Lastly, as you download the dependencies once, it reduces the overall application size.

Sharing data between components

This is the make or break piece of the puzzle. The most important responsibility of the platform application is the routing and state management. If you are using ReactJS, it’s quite well done with React-Router and Redux. Each component should have its own state, accessible by the parent app. The platform application should only pass the history to each component, to be able to read the URL parameters and push to the browser history. Any other interfacing should be done by passing handlers to the child components. The moment your child component needs too much state from the parent, you’ve designed something wrong.

Benefits & Drawbacks

The good

- Smaller and separate codebases, allows for teams’ tech stacks evolve in their own pace.

- Decoupled and smaller deployments leading to smaller chance of breaking everything

- If one team gets the stack wrong, easier to migrate one piece than the entire frontend

- More independent teams and practices

- Single dependencies download (Build-time integration approach)

The bad

- More fragmented infrastructure, more moving parts to maintain

- Redundant data fetches, if the inter-component data share is not done correctly

- Code duplication

- Losing track of who has released what and when

- Multiple dependencies download (Run-time integration approach)

Wrapping up

Micro frontends promotes the need for full-stack teams, which is a step towards avoiding the “I’ve always been a backend developer” situation. Nonetheless, this approach is not a panacea or a substitute for good design practices. For it to work well, you rely even more on a well defined CI/CD pipeline and responsibilities delegation.

I hope this post made some of the skeptics of frontend development a bit more optimistic or at least convinced a backend developer to try building a user interface component. If you got up to this point and enjoyed this post, please share!

Thanks for reading!

0 Comments